Entrance of Köpenicker Straße 6a–7 in Berlin-Kreuzberg

Rear wing of Köpenicker Straße 6a–7: Here, forced laborers had to work; the fourth floor was destroyed by bombs in March 1945 and wasn't rebuild later on

Salamander

My notice of forced labor assigned me to Salamander A.-G., Reparatur-Betrieb, Berlin SO 36, Köpenicker Str. 6a–7. From now on I spent my days in a factory located in a backyard near Warschauer Brücke.

I stood in front of heavy barrows with iron wheels which looked like plump shelves. They were used to transport shoes back and forth between workers in the hall. The barrows were pushed to me from the left, loaded with worn out, crushed, and sweaty shoes. They were in need of repair, and I had to check which repair was to be done. I had to examine the shoes, determine their damage and sort the pairs into other barrows: to be stitched, glued, resoled, and so on. When a barrow was full I wheeled it to where the shoes were stitched, glued, or nailed.

A woman was in charge of the right-hand aisle. She always carried a bendable stick to point to damaged shoes without having to touch them. She carried the stick like a tamer carried his whip. The overseers were members of the SS, as was the woman in charge of the right-hand aisle. They watched us and made sure that we did not do anything but work. “Us” were Polish shoemakers, women from Serbia, French workers, Jewish women, girls like Hannchen and me.

Nobody was allowed to talk to anybody. If one was required to stand, nothing was permitted but to stand. If one was required to sit, nothing was permitted but to sit. We did not fear being beaten with the stick, but the threat of being sent to a concentration camp was always palpable – that is what had happened to the girl who had checked the shoes and wheeled the barrows here before me.

The SS hag had come up with something for us: Above the stitching at the heel, many shoes had a leather strip attached by stitching which came loose after long wear. If this was the case, it was glued on again using a glue called “Ago”. I had to check whether or not the stitched seam still held tight. To check this, a tool was usually used which looked like a broken knife. I thought the overseer would give me the tool. “Go! Begin!” – “With what?”, I asked. “Don't you have fingernails?” So I slid a fingernail under a leather strip and checked its tightness. “I told you so! You follow good.” After a few hours I realized the trick to doing it. When I sensed that my fingernails were rubbed and the skin broke and became sore, I changed fingers and gave the sorest ones a rest. I changed fingers too quickly, so that all became infected. Then I came up with a new plan: I used only one finger a day. I lasted three days, before I – again – switched fingers too quickly. Shortly after the white of the nails became damaged, the skin swelled, broke, got infected and began to fester. My fingertips were a bloated mess.

Nearly all shoemakers in the workshop were Poles. One of them, Jacek, pushed the barrows to me, when a new batch came or when the repairs had been done: the barrows with the Ago glued shoes from the workers close to the stairs as well as from other places of the workshop. Jacek hadn't talked to me much yet. Only on my first day. “I'm Jacek. And you?” – “Vera.” Jacek was guarded. Not due to the speech interdiction. He was suspicious of me.

Shortly after Hannchen and I stood in front of the SS officer, Jacek asked while pushing the barrow to me: “Why are you here?” – “I'm assigned.” That likely didn't mean a thing to him. When he brought the next barrow, he asked again: “Why are you here?” – “Because I'm a half-Jew.” – “I don't understand. Jew or not Jew? What's half Jew?” – “My mother is a Jew. My father is a Christian.” – He couldn't stay any longer, the overseer came closer. But with the next barrow he asked another question: “You – German?” – “Yes.” And again: “But why are you here?” How I could explain to Jacek why I was there? I didn't understand it myself. But Jacek said when he came back: “I understand.” Now I have a question: “Do you believe me, Jacek?” – “Yes.” – “Because of earlier, below the stairs?” – “No. Because ... your hands. And you are frightened, the other girl too.” In this manner I talked to Jacek, the Polish shoemaker, more than a month. We conducted serialized short dialogues. If it hadn't been for Jacek, I'd have used the thin layer of horny skin of my fingers again to slide them under the leather strips. The first thing he said to me the next morning was: “My friends say: All shoes with leather strips go to the Ago glue station. Do you understand?” – “No examination? All shoes straight onto the Ago barrows?” – “Right. Hands must heal.” When Jacek brought the next barrow the dialogue was very short: “Thanks, Jacek.” He only nodded.

There were rumours in Salamander's hall that the German women should be sent to East Prussia to dig out trenches. Then it was heard: Behind the Oder river. We were twelve women: except Hannchen and me, the women who were Jews married to Aryan husbands. At lunchtime in the canteen, while spooning our soup, Hannchen told me: “The women say that the two of us would be the first to know that they are coming to get us. We can see the hall entrance, and we are to give a sign when we notice anything.” – “What for? Nobody can run away from here.” – “Nevertheless. Promise. It'll calm them, they say.” – “Well. I'll pay attention.”

“Vera, when they are coming to get us, are we going to stay close together?” I hugged Hannchen. It felt good to touch somebody. “If we can't go home anymore, that'll be hard, Hannchen. Now, out in the cold, digging out trenches. We have to think of something.” – “From tomorrow on we'll put on double layers of everything, stockings, shirt, underpants. And into the bag that we must hand in downstairs we put a sweater and things we absolutely need.” – “Curd soap and something to sew.” – “As long as we'll stay together”, Hannchen closed the conversation.

The only recovery was the lunch break. We got warm soup with potatoes or noodles. The soup and the tramway ticket were our pay. Each day at lunchtime we went into a room which was set up as a canteen. Still, we could sit on benches and put our bowls onto tables. Here, we, the Germans, were allowed to talk amongst ourselves. But it was forbidden for us to speak to the men and women who were marked as “OST-Arbeiter” with a patch on their jacket.

We reached the canteen through a windowless hallway. The hallway had two dark niches closely guarded by the SS men. In those niches, Soviet prisoners sat on the floor. They were lead into the niches before we passed the hallway, and they were still there when we returned to the hall. There they sat and ate potatoes boiled in their skin. They each had a handful of it, nothing else. The same day after day. They ate the potatoes with peel, and I only wished that the potatoes at least had been hot. At least we had the canteen with tables, benches and windows, with bowls and spoons. We passed those men and knew nothing about them. They weren't let out of sight. I never found out what or where they worked at Salamander.

To whom did the shoes at Salamander actually belong? There just had to be a great many naive people who gave their shoes – in this period a precious possession – to a repair service and reckon that they get them back, repaired. And where were Salamander's counters? People who gave their loafers to have them repaired seemed to have no special wishes. And the people who served them handled the shoes very carelessly. They marked no shoe, not one was tagged with a number, a label, or a stamp, although the shoes had to be transported through the entire city and back, since their owners would have get them back again. Where were these customers? Where did the shoes come from and where were they sent to?

This day and age, decades later, someone may buy Salamander shoes. I, for one, that's certain, won't wear shoes with this name. If I hear this name, I have to remember the shoes without owners. It's not true that time is the great healer.

Vera Friedländer

The text is a shortened form of the chapter »Salamander« from the book »Späte Notizen« (Late Notes), Verlag Neues Leben, Berlin 1982 – published in 1998 at Agimos-Verlag Kiel and in 2008 at Trafo-Verlag Berlin with the title »Man kann nicht eine halbe Jüdin sein« (It's Impossible to be Half a Jew).

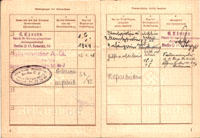

Vera Friedländer's “Arbeitsbuch” (job placement book) with the stamp »Salamander A.-G. – Reparatur-Betrieb – Berlin SO 36, Köpenicker Str. 6a–7«

Through the entire war Vera Friedländer (71) worried about herself and her family. Her mother was a Jew, her father a Christian. But while her father has been put in a prison camp her mother remained undisturbed. Until now she doesn't know why. She assumes that a resistance group in the Berlin employment office for Jews walked off with her mother's registration card.

For a while Vera Friedländer worked – voluntarily and paid – as a shorthand typist at an arms manufacturer until early in 1945 when her boss received the notice of forced labor which assigned her as an unpaid, unskilled worker to the repair service of Salamander A.-G. at Köpenicker Straße. There – Friedländer reports – she worked “together with 50 to 60 people”, Polish shoemakers, Frenchmen, Serbian and Jewish women – until March 18th, 1945, when the building had been partly destroyed by a bomb. Afterwards she was assigned to a leather factory. All these stages are documented in her job placement book.

After the war, Vera Friedländer began to work in the GDR first as an editor and later on as a professor for linguistics at the Humboldt University. When she tried to make an application for acceptance as a Victim of Fascism, she was told at the office: “Why? Nothing has happened to you.” Since 1990 she receives a small pension as a “racially haunted”.

Today Vera Friedländer is head of a language school in Berlin. Some time ago, she again visited the rooms of the former repair service at Köpenicker Straße in Berlin-Kreuzberg. What the bombs spared exists to this very day. Most of the rooms are empty. When she expands her language school, she would like to rent those rooms and affix an identification plate at the entrance as a reminder of the past, and so that Salamander can no longer deny that this repair service had ever existed.

taz from December 14th, 1999, page 3 • By courtesy of taz – die tageszeitung

The list of foreign civil worker camps which was compiled periodically from 1940 on by Polizeiamt Mitte (police office Berlin-Mitte) contains »Salamander-Schuhe, SO 36, Köpenicker Straße 6–7«

Already the Berlin address book from 1937 contains the Salamander repair service at Köpenicker Straße 6a

Pre-collection letter to: Salamander

Do we need Salamander shoes?

Salamander doesn't know a thing. The corporate group passes enquiries directly to the historian Hanspeter Sturm who edited the Salamander history with the sugar-coated title “Sie hatten schützende Hände” (They had protective hands). Here, he describes the commendable behaviour of the corporate management during the Nazi era: “All Jews who were employed with Salamander before the war could begin again after the war.“ He says that thanks to the “protective hands” of president Alex Haffner, no Jew had perished, the corporate group only employed 284 French prisoners of war as forced laborers, and that otherwise there had been only so-called contract workers from France and Greece who had been paid, as were their German colleagues.

About the repair service decribed by Vera Friedländer in her autobiographical report, the historian knows nothing. “Salamander shoes don't need repair”, he laughs. Also the press relations officer Elvira Saverschek never heard about it. She researched in the land register and declared: “There has never been corporate property at Köpenicker Straße.” That's right. But a Berlin address book from 1937 indicates Salamander A. G. as the licensee of a repair service at Köpenicker Straße 6a. And Vera Friedländer also retained her job placement book. The address above is clearly legible in the Salamander stamp.

“This could only have been a local business”, the historian Sturm says. And Elvira Saverschek explains after reading Vera Friedländer's report: “As a start, we'll take our time to consider what Ms. Friedländer had fabricated here.”

Volker Weidermann

taz series: Pre-collection letter

taz

from December 14th, 1999, page 3 • By courtesy of

taz – die tageszeitung

November 10th, 2011, in Kornwestheim: Anne Sudrow and Vera Friedländer

Vera Friedländer's book: Ich war Zwangsarbeiterin bei Salamander (I was a forced laborer at Salamander)

“My fingertips were a bloated mess”

“Travelling to Kornwestheim wasn’t easy. I had to force myself to do it”, Vera Friedländer says. As a young woman, the 83-year-old had been a forced laborer at a Salamander repair service in Berlin. Invited by the Protestant Church in Kornwestheim, she now spoke about her experiences.

More than 50 years after the initial injustice suffered by Vera Friedländer, the Salamander company added insult to injury, when confronted in 1999 by a journalist with Friedländer’s story, by claiming that “There has never been a repair service in Berlin.” This was an affront to an elderly woman who, in early 1945, for several months was forced to inspect Salamander shoes for their need to be repaired with her bare nails because she was denied the adequate tools. Until her fingers were sore and ulcerated to the point where they were just “a bloated mess.”

More than 60 years after the injustice, approximately 80 women, men and teenager at the Protestant John Parish Hall – many from the religious community, some from the historical society, along with Walter Habenicht and Friedhelm Hoffmann, the only two from the church council, and only town archivist Natascha Richter from the local government – listened to Vera Friedländer’s account of her suffering during her time at the repair service at Kopenicker Straße 6a–7 in Berlin. The repair service that the company denies even existed, had been listed in the Berlin phone books in the 1930s and 40s. The company’s denial continues even though Vera Friedländer’s job placement book shows the stamp of »Salamander A.-G.«, and in the face of evidence that Salamander even had company-owned camps for its forced laborers.

As the daughter of a Jewish mother and a religious Catholic father, Ms. Friedländer was nevertheless required to do forced labor, although thanks to her father, she was not sent to a concentration camp. Despite the pressure from the Nazis, he refused to divorce his wife. He accepted, instead, being deported to a work camp. “In doing so, 3000 upright men in Berlin saved their families’ lives. Their relatives enjoyed a certain degree of protection. If my father had divorced my mother, we would all have been lost.” Lost like 24 of her 27 relatives who were killed during the Third Reich. Little Bella, for example, shown in Vera Friedländer’s arms in a 1942 photograph on the cover of her autobiography, “It’s Impossible to be Half a Jew.” Bella with a plaid dress and curly hair, a shy two year old in the photo, died in January 1943 in the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

“It is not the fact that I had to do forced labor that impels me to mention Salamander again and again,” says Vera Friedländer. “The shoes are the reason why.” With respect to all the shoes that had been repaired in the repair service, Vera Friedländer had wondered for a long time where those shoes actually came from. After reading Anne Sudrow’s book, »Der Schuh im Nationalsozialismus« (The Shoe in the Nazi Era), she is certain, she says quietly that “a large number of them were shoes from the deportees, shoes from the concentration camps, a precious commodity at the time.” After repair, they were either distributed to people who had been bombed out, or to people who had been settled in the occupied territories, or were sold to German industrial and agricultural enterprises.

Gentle in tone, but clear and concise on the matter, Vera Friedländer takes apart Salamander’s later version of the company’s history during the Third Reich. The corporate historian, Hanspeter Sturm, attested to the company’s “flawless clean record,” although between 1933 and 1945 Salamander had developed into the leading shoe manufacturer during the Reich. The company chronicle attributes the success to the “skillful political and economic tactics of the Director General Haffner.” It wasn’t mentioned that this success came, in large measure, from the quick adaptation to the Nazi regime, from the urgent and systematic “Aryanization” process, from the exploitation of cheap forced laborers and from the murderous experiments on humans on the shoe test track at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

The surviving witness, Vera Friedländer, quotes from the Salamander company chronicle that thanks to the “protecting hands of Haffner” no Jew employed by Salamander had perished. “Maybe this is true for the few Jewish employees in Kornwestheim, but what about the employees from the neighborhood or from other production sites?” Friedländer asks. She has researched some biographies of Kornwestheim residents of the time. “Tradesman Julius Löw was dismissed in 1938, then worked as an unskilled worker, survived Theresienstadt. Frida Singer survived because her husband, a senior staff member at Salamander, didn’t divorce his wife and had been sent to a prison camp of the Organization Todt – like my father. The family Spenadel, Fritz Cahn, Saly Pressburger all successfully emigrated to the UK or the U.S.” Euphemistically, the chronicle refers “in typical Nazi terminology, to external migration” and the “good Salamander contacts at the top of Reich and party organizations” which would have enabled that. “You can see it the other way around,” says Vera Friedländer. “These people had to give up all their assets, or needed a guarantor in order to emigrate.”

Furthermore, Vera Friedländer names Michael Wolff, former host of the Swan Inn, a waiter in 1938, who was not protected by Salamander but by NSDAP district leader Otto Trefz, Reich commissioner in Latvia starting in 1942. “He has covered for Wolff since the struggle against social democrats and communists in 1931,” says Friedländer. However, the “half-Jew” Oscar Epstein employed by Salamander had managed to adapt. “He was also responsible for important physical and chemical innovations – Salamander needed him.”

For a long time, she didn’t want to have to do anything with Salamander and Kornwestheim, says the emeritus professor of German language at Berlin’s Humboldt University, whose history also provides content for a play, “But now I’m glad I came. I didn’t expect that much support.”

It is a goal of the 9th November working group to present life and suffering true stories of the previous generation, says Isolde Gneiting-Tränkle, the host. And the Rev. Fraukelind Braun gratefully thanked Vera Friedländer by saying that “you did come into this city, which is connected so much with the name Salamander” and the difficult memories you bear.

Susanne Mathes

Kornwestheimer Zeitung from November 14th, 2011, page III • By courtesy of Kornwestheimer Zeitung

The main persons responsible at Salamander

Leading managers of Salamander AG during the Nazi era:

• Alexander Haffner as chief executive officer 1930–1955

• Jakob Sigle as chairman of the supervisory board 1930–1935

• Ernst Sigle as chairman of the supervisory board 1935–1956

Ernst Sigle and his older brother Jakob were, as owners and as deputy and chairman of the supervisory board, together with the chief executive officer Alexander Haffner, mainly responsible for the Aryanization of Salamander AG in 1933 and its direct beneficiaries. Ernst Sigle and Alexander Haffner were jointly responsible for the Aryanization of the leather company J. Mayer & Sohn in Offenbach and the shoe factory Bernhard Ross in Speyer in 1936 as well as the acquisition of shares in the Aryanization of the leather factory Sihler & Cie. AG in Zuffenhausen in 1937. They were also jointly responsible for both the exploitation and often inhumane treatment of thousands of forced laborers during the Second World War by Salamander AG and for the “further utilization” of hundreds of thousands of pairs of shoes of those murdered in the extermination camps in the Salamander repair service in Berlin-Kreuzberg.

As a representative of what was then Germany's largest shoe manufacturer, Ernst Sigle was a co-decision-maker on the Special Committee on Wehrmacht Footwear for the tests on the "shoe test track" in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. He and Haffner were partly responsible for the mistreatment and murder of thousands of prisoners by the SS on the “shoe test track”. Documents from the state authorities in the Federal Archives in Berlin show that Salamander's leading managers were not only involved in the decision to build a test track in the Sachenhausen concentration camp at all and to run it with prisoners. Salamander was also one of the first companies to voluntarily send materials and shoe models to the concentration camp for testing from June 1940. There is evidence of visits to Sachsenhausen concentration camp by managers of the Salamander company. There they inspected the tests and had direct contact with the concentration camp prisoners, who had to line up in front of them to inspect the shoes. Direct concentration camp connections of the management can also be proven in other points. For example, members of the top management in the war economy held leading positions in various technical committees that dealt with the evaluation of the concentration camp experiments for almost five years. Men like Ernst Sigle, Angelo Hammelbacher, Robert Eichenlaub, and Hans Dietmann therefore knew exactly that concentration camp prisoners were being abused here for their own purposes. Salamander paid a “user fee” of RM 6 (Reichsmark) per day and prisoner to the Reichsamt für Wirtschaftsausbau (Reich Office for Economic Expansion) for the tests on the “shoe test track”.

In the city of Kornwestheim – the headquarters of Salamander until 2004 – the secondary school is named after Ernst Sigle as well as a square and a street after Jakob Sigle and Alexander Haffner.

A distinctive word of the Nazi language: „Nationalsozialismus“ (“National Socialism”)

The Nazis had already coined this word before 1933 in order to win over the masses who imagined that socialism was something worth striving for. They promised them a national socialism. That was fraud. For the nation led them into war, and they fought socialism.

Unfortunately, today almost everyone in our country uses this word as if it were socially prescribed. I call the system of Nazi rule the word that is internationally customary: fascism, German fascism. All nations around us call it fascism. Only here in Germany is this lying, demagogic word “National Socialism” („Nationalsozialismus“) used. I find that very regrettable.

Vera Friedländer

on October 10th 2018 at Gleis 17 (platform 17) of the railway station Berlin-Grunewald and on March 12th 2019 at the Museum Hotel Silber in Stuttgart

Vera Friedländer speaks at the Gleis-17 deportation memorial on 18 October 2018 (photo: www.markopriske.de)

We grieve for Vera Friedländer

On the evening of 25 October 2019 Vera Friedländer died in Berlin at the age of 91. She has always not only spoken out against anti-Semitism, but has also shown a consistent attitude against intolerance and historical clutter.

Since 1947, Vera Friedländer belonged to the VVN, today VVN-BdA (Association of Persecuted Persons of the Nazi Regime—Association of Antifascists).

Her grave is at the cemetery in Woltersdorf near Erkner.

Inauguration of a memorial plaque at the building Köpenicker Straße 6a–7 on 21 July 2020 (with veiled faces due to the Corona pandemic)

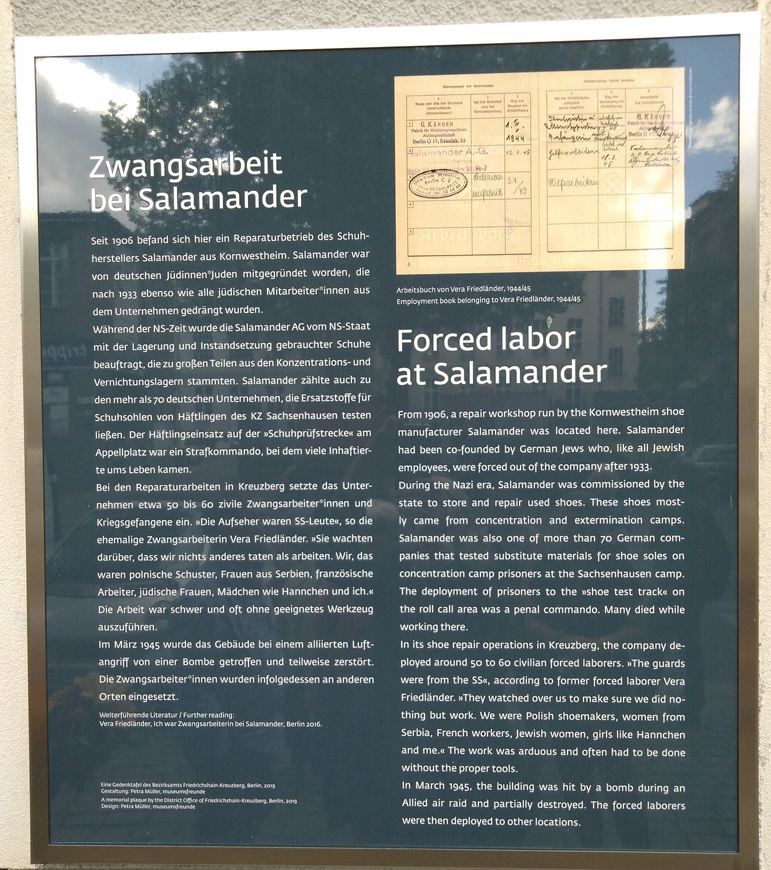

Memorial plaque for forced labor at Salamander (top right, copy of Vera Friedländer's job placement book)

Salamander's dark past

Kornwestheim – For ten years she fought, together with her two sons and her grandson, for a memorial plaque to be placed in front of the house at Köpenicker Straße 6a–7 to commemorate the fate of the many forced laborers from the Berlin Salamander repair service. The plaque has been hanging since last weekend, but Vera Friedländer has not been able to experience this. In October of last year, she had died at the age of 91.

Among others, the Kornwestheim Stolperstein Plaques Initative, the Kornwestheim Protestant and Catholic church congregations and the Ludwigsburg district association of the Association of Persecuted Persons of the Nazi Regime had donated money for the memorial plaque. In the end, however, the district administration of Berlin-Kreuzberg/Friedrichshain covered the costs. Before the unveiling of the memorial plaque, Ole Hemke, the grandson of the deceased, read out a letter from Isolde Gneiting-Tränkle. She and the „Arbeitskreis 9. November“ (Working Committee November 9th) of the Kornwestheim Evangelical Church Parish had already invited Vera Friedländer to give a lecture in Kornwestheim in 2011, which attracted much attention. Gneiting-Tränkle reminded the audience that it was only with the visit of the Berliner that an impulse was triggered in Kornwestheim, which led to a more critical view of the history of the Salamander group, which had been so “beautiful” until then. During her first visit, Friedländer reported that the existence of the repair service in Köpenicker Straße had been denied. Friedländer found attempts to get reparations deeply offending. During her second visit to the municipal library, which was overcrowded this time, with the presentation of her book „Ich war Zwangsarbeiterin bei Salamander“ (I was a forced laborer at Salamander), Vera Friedländer triggered a critical discussion about the company's role in the Nazi era. Gneiting-Tränkle expressed her thanks for this once again in her welcome address. “At last, after so many decades of silence and reinterpretation, the people of Kornwestheim had been awakened from their history-forgotten sleep and wanted to know the truth about the darkest chapter of their city's history.” Friedhelm Hoffmann, spokesman for the Kornwestheim Stolperstein Plaques Initiative, who had accepted the invitation to Berlin, also reminded in his speech that the Stolperstein Plaques Initiative would probably not exist today without the impulse of Vera Friedländer. In addition, the discussion about the naming of Kornwestheim institutions had been initiated. On the one hand, the name of the Hanspeter Sturm sports hall has been criticized. The Stuttgart police commissioner and head of the Salamander track and field athletics team has reappraised the history of Salamander and published a company chronicle as early as 1958. In doing so, he left out the topic of forced labor. On the other hand, the question arises in the city whether the Ernst Sigle High School should keep its name. Ernst Sigle, brother of Salamander founder Jakob Sigle, was chairman of the supervisory board at Salamander from 1935. He also had a say in the establishment of a shoe test track in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Salamander was among the first companies to send shoe models to the concentration camp for testing in 1940.

In his speech in Berlin, Hoffmann said that he was firmly convinced that the Salamander story had to be rewritten. One would cherish the memory of Vera Friedländer and ensure that this memory would also be visible in Kornwestheim in the future, said the former city councillor of the Linke party.

The plaque informs in German and English about the forced labor at Salamander and shows a photo of Vera Friedländer's job placement book.

Kornwestheimer Zeitung from August 8th, 2020 • By courtesy of Kornwestheimer Zeitung

And today?

“The world was almost won by such an ape!

The nations put him where his kind belong.

But don't rejoice too soon at your escape –

The womb he crawled from is still going strong.”

(The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui by Bertolt Brecht)

The Nazi Party once began just as seemingly harmless as the AfD does today.

(drawings and photos of the La Hille children

given by Vera Friedländer)

Nazi Forced Labor Documentation Centre

Contact

Herbert Hemke, Berlin, Germany

hhemke[[at]]posteo.de